Twilight Capitalism – A Book Review

Twilight capitalism: Karl Marx and the decay of the profit system is the best book on Marxist political economy in 2021. Authored by Murray EG Smith, Jonah Butovsky and Josh Watterton, these Canadian-based Marxist economists have delivered a comprehensive and often original analysis of global capitalism in the 21st century.

As the title of the book suggests, the authors argue that capitalism is now in its twilight phase before its demise as a functioning social system. To prove this thesis, the authors deal with all the Marxist theories of crises in capitalism, answer the critiques of the Marxist analysis by mainstream and heterodox economists and provide original empirical evidence to support the Marxist paradigm. As such, this is an ambitious book, but its ambition is successfully achieved.

As the authors start by saying, “this book is a hybrid of sorts”, namely an updated version of previous work by Murray Smith, namely Global Capitalism in Crisis: Karl Marx and the Decay of the Profit System published in 2010 and also Smith’s excellent 2018 book, Invisible Leviathan, which takes the reader deftly through the debates over the validity of Marx’s law of value.

The book begins with the ‘here and now’ – and so with COVID pandemic. Over two chapters, the authors spell out the origins and course of the pandemic, making, in my view, a key point. The COVID slump may have been triggered by a global health crisis, but even before the pandemic struck, global capitalism had been in a period of depression exhibited by low economic growth and poor productive investment and, above all, by low and falling profitability of capital – the key ingredient of ‘twilight capitalism’.

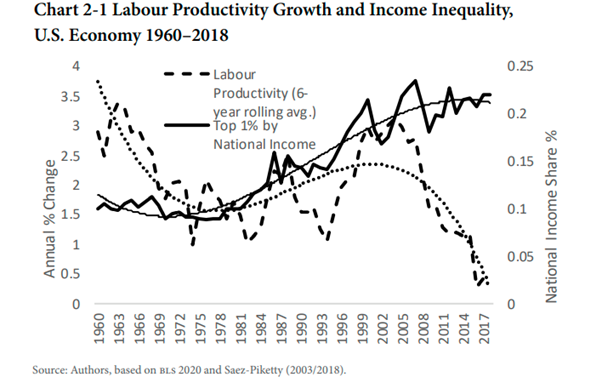

In the previous four decades before the pandemic, inequality of incomes rose as most of the gains in productivity did not ‘trickle down’ to labour.

The average annual rate of growth of labour productivity fell over the long term (largely due to a slowdown in new fixed capital formation), but the share of income earned by the top 1 percent increased dramatically, rising almost without interruption from about 12 percent in 1985 to about 22 percent in 2017. On the other hand, wages, particularly for the bottom 80 percent to 90 percent of income earners, either stagnated or declined in real terms between 1970 and 2015.

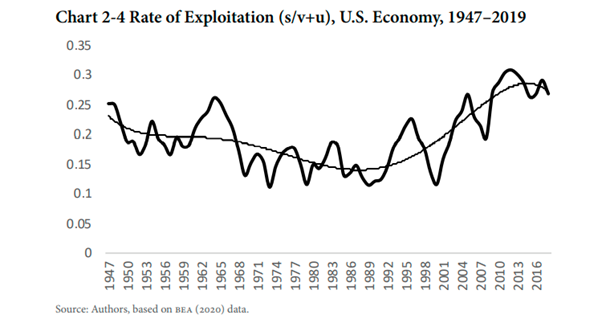

Smith et al offer a Marxist insight into this rising inequality of income and wealth since the early 1980s – namely a rising rate of exploitation of labour by capital, as measured by the surplus appropriated by capital in profits, interest and rent (s) compared to the wages of productive and unproductive (but necessary) workers (v+u).

In the next three chapters the authors get down to the nitty-gritty of Marx’s account of capitalist crises, both theoretically and empirically. The key underlying cause of periodic capitalist crises is the recurring problem of insufficient production of surplus value, a problem that has continually mutated and worsened since a new material basis for capital accumulation was established in the aftermath of World War II. The financial crisis of 2007–09 was the outcome of a decades-long effort on the part of the capitalist class, in the United States and elsewhere, to arrest and reverse the long-term decline in the average rate of profit that occurred between the 1950s and the 1970s.

The Great Recession was the cumulative and complex result of a series of responses by the capitalist class to an economic malaise that can be traced to the persistent profitability problems of productive capital — the form of capital associated with the “real economy.” The authors present the evidence of numerous empirical studies by Marxist economists, and their own work on the US and Canada, some of which has been published in World in Crisis (2018), as edited by Guglielmo Carchedi and myself.

The authors explain that the characteristic form of capitalist economic crisis is overproduction. Overproduction means that not enough commodities can be sold (or markets cleared) at prices that permit an adequate profit margin; and since profit drives capitalist production, economic growth must slow or even decline, throwing large numbers out of work, bankrupting many firms and rendering much productive plant idle.

But overproduction is only a description of a capitalist crisis, not the cause. As the authors say, “according to Marx, a variety of unique circumstances can trigger crises of overproduction; however, the most important recurrent cause is the tendency of the rate of profit to fall due to an overaccumulation of capital and inadequate production of surplus value. If overproduction involves the social capital’s inability to realize the full value of the total commodity output, this “crisis of realization” is ultimately the surface manifestation of a crisis of valorization — a crisis in the production of sufficient quantities of new value and surplus value.”

They involve Marx’s double-edge law of profit, namely that “a fall in the average rate of profit need not always precipitate a conjunctural crisis of capital accumulation, such a crisis is not always preceded by a particularly sharp fall in the average rate of profit. A fall in the mass of profits combined with other disturbances may suffice.” The fall in the mass is a product of a fall in the rate of profit.

The causes of the fall in the profitability of capital in the major economies over the long term are much debated by Marxist economists. The authors defend the view that the main determinant is a secular rising organic composition of capital (increased investment in means of production over wages of employment). As the organic composition of capital rises, the average rate of profit on capital will fall.

In promoting Marx’s law of profitability, the authors deliver a significant critique of other explanations, in particular that of Robert Brenner in his signature work of the late 1990s (Uneven Development and the Long Downturn: The Advanced Capitalist Economies from Boom to Stagnation (New Left Review 229, May–June 1998), which dominated thinking at the time. Smith et al: “Brenner’s approach is sharply at odds with our Marxian theorization of a valorization crisis and is criticized on that account. In particular, inasmuch as Brenner’s thesis rests upon a concept of “realization crisis” that has much more in common with the Keynesian tradition than with Marx’s theory, our critique of Brenner serves the larger purpose of revealing the basic incompatibility of even the most “left” versions of Keynesianism with Marxism.”

I would add that, for me, Brenner, in rejecting Marx’s law of a rising organic composition of capital as the underlying force for falling profitability, falls back on the position of Adam Smith, namely profitability falls because of increased competition between capitals. The Smithean cause opens up the response that, if only wages did not rise too much, profits can stay up and so capitalism can avoid crises.

The ‘profit squeeze’ theory of crises is the reciprocal of Brenner’s thesis. A theory of crises based on wages squeezing profits was popular among Marxists in the 1970s, but has lost its traction now as the rate of exploitation of labour by capital has risen sharply in the 40 years; and yet average profitability is near all-time lows. Only post-Keynesians, following Keynesian-Marxist Michal Kalecki, now talk about ‘wage-led’ (wages too low) or ‘profit-led’ (profits too low) explanations of crises. This neo-Ricardian explanation of crises no longer has support among most Marxist economists, given the evidence of profitability decline, particularly in the 21st century.

There is an important chapter on alternative theories of crises, where the authors critique theories from various ‘radical heterodox’ economists. Popular radical economists like Mariana Mazzucato and Stephanie Kelton are taken to task here. These economists ignore or reject Marx’s value theory and instead focus on Keynesian ‘lack of demand’ analyses, ‘market failure’ or financial ‘instability.’ But they do not offer a coherent explanation of crises or sufficient empirical evidence to support these alternatives.

The current popular alternative to Marx’s law of profitability as the underlying cause of capitalist crises is ‘financialisation’. And Smith et al agree that there has been a massive expansion of the financial and property sectors (FIRE) and FIRE profits in the last 40 years. But they show much of this is fictitious, ie it is paper profits that eventually won’t be ‘realised’ from value created in production. What happens in the value-creating sector will be decisive.

The authors comment: “in our view, the financialization phenomenon is yet another perverse expression of the profitability and valorization problems of productive capital. Financialization has not “transformed” capitalism in some fundamental way, allowing it to dispense with the exploitation of productive wage labour as a means to generating profit. On the contrary, the phenomenon testifies to the decay of the profit system and the frenzied efforts of powerful circles within the capitalist class to accumulate immense fortunes without contributing (even in indirect ways) to the production of commodities and surplus value.”

Financialisation is the consequence of the malaise of the productive sector. Capitalists now desperately search for profit from buying and selling money and credit rather than from exploitation of labour in production. The authors remind the reader of Marx’s observation in Capital Volume Two that, to the possessor of money capital, “the production process appears simply as an unavoidable middle term, a necessary evil for the purpose of money-making.” As Engels commented: “this explains why all nations characterized by the capitalist mode of production are periodically seized by fits of giddiness in which they try to accomplish the money-making without the mediation of the production process.”

It is not just in economics that a failure to use Marx’s value theory leads to a misunderstanding of the cause of crises; it also has political consequences on policy and the authors spend some ink considering the crisis in the radical left, particularly in North America. They make the point that Marx’s law of profitability is not only the basis for understanding recurring and regular crises in modern capitalist economies, but it also “provides an extremely powerful but also essentially simple argument in support of the proposition that the development of the forces of production under capitalism points with inexorable logic toward socialism.” The secular decline in profitability implies the transient nature of the capitalist mode of production as crises intensify. Indeed, the expansion of robots to replace labour in production will accelerate that.

This brings the reader to the final chapter on socialism. Albert, Gindin, Mandel and others are cited in an unfortunately rather short discussion of the key issues of democratic planning, in which the authors offer “a critical historical retrospective on what was sometimes called “actually existing socialism” in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, a consideration of some recent “blueprints” for building a socialist society and an argument in support of “proletarian-democratic central planning as a necessary element in the transition to a global socialist civilization truly worthy of the name.”

In the big debate on the nature of China, Smith, Butovsky and Watterton do not dodge the issue. I quote at length: “China is not now and never has been fully socialist. Rather, it is best understood as a transitional socio-economic formation, one that has combined elements of capitalism and socialism since the victory of the Chinese revolution in 1949. To be sure, the balance of these elements has shifted massively over time, and there is unquestionably a very real possibility that the capitalist elements may yet prevail over the socialist ones. But a convincing case has not yet been made that a “capitalist counter-revolution” has already occurred. The thesis that China has been completely reabsorbed into world capitalism, that the Chinese party-state bureaucracy is now an instrument of capitalist class rule and that the Chinese economy is subordinate to the law of value is simply not credible. What’s more, to credit China’s rapid economic development and modernization to the restoration of capitalism is to give considerable ground to those who reject the Marxist thesis that, by the twentieth century, capitalist social relations had become a brake on the development of the productive forces of humankind.”

As humanity faces impending disaster from global warming and climate change, Smith, Butovsky and Watterton pose what they call “a difficult paradox” for socialists. “In order to win a world in which we can truly realize our most authentic human capacities, we need to act in ways that are hard-headed, strategic and disciplined. Capitalism cannot be reformed, tweaked or reoriented. Rather, it must be replaced … and that, quite simply, will be no easy task. The existing capitalist ruling classes will do everything in their power to prevent the destruction of the system to which they are wed. We must be no less determined in our efforts to prevent them from having their way.”