Russia’s Emergence as an Imperialist Power

Examining Recent Trends in Foreign Investment

— Decker, 27 March 2014

Russia inherited much of its economic base from the Soviet Union, which by unplugging from global capitalism and employing centralized planning was able to create a modern industrial economy. Although crude in some respects, it was quite advanced in others (military technology, space/aviation technology, chemicals, etc.). Capitalist counterrevolution dislocated the economy, which went into a nosedive for about a decade.

In our 2002 article on Russia’s “Capitalist Dystopia” (which was based on evidence from the country’s “basket case” days), we noted that “Russia today has attributes of both a great power and a semi-colony, just as it did under the Czar.” While the inheritance from the Soviet Union in military, economic and geopolitical terms was significant, the Russian bourgeoisie was unable to make use of these “great power” capacities to consolidate an imperialist state roughly comparable in relative stature even to Tsarist Russia. We predicted that the “semi-colonial” features of the country would be strengthened:

“Despite immense natural wealth and a substantial cadre of skilled workers, scientists and engineers, thus far the re-integration of the former Soviet republics into the capitalist world market has produced mass impoverishment and the destruction of much of the pre-existing educational infrastructure and industrial capacity. Nigeria provides a closer model for Russia’s future under capitalism than Sweden or Germany.”

Yet even as we were writing these lines, the situation was changing due to a combination of rising energy prices and the cohering of a strong regime based on an indigenous super-rich “oligarchy” running a highly monopolized economy—a regime, independent from foreign imperialist domination, committed to reversing Russia’s decline and transforming its “great power” attributes into the basis of an imperialist state. In the course of the 2000s, revenues from oil and gas sales were channeled into investment both at home and abroad, while some of the stronger industries inherited from the Soviet Union (along with corporations in new sectors) maintained and expanded markets and investments beyond Russia’s borders.

In his 2013 book, The BRICS and Outward Foreign Direct Investment (Oxford University Press), David Collins observes that an oligopolistic financial-industrial structure allowed the Russian capitalist class to leverage profits made through high energy prices into expanding foreign investments:

“During the early 2000s there was a strategic shift in the domestic business environment that led to general improvements in [Russia’s] economy and saw the creation of SOEs [state-owned enterprises] in key industries, either with the assistance of public finance or through more efficient administrative measures. During the period since 2000, the Russian economy has become largely concentrated in the hands of several large corporations. It is believed that the high concentration of income in the Russian economy was one of the major motivators behind the globalization of Russian firms. In 2001 the Russian investment bank Troika Dialog calculated that around 70 large financial and industrial groups controlled 40 per cent of the Russian GDP.”

…

“Modern Russian MNEs [multinational enterprises] now display a high degree of horizontal and vertical integration of production capacities which also include distribution networks and banking, linking services to non-services outward FDI. Most Russian companies operating abroad retain strong ties with domestic natural resources. Until recently, most Russian MNEs were in the oil and gas, metallurgy, and electricity generation and distribution industries. Russian firms have exploited the ties to their natural resources base as collateral to raise loans for FDI, particularly during periods where the prices for these commodities were highest.” [pp.49-50]

While capital export from the highly monopolized energy sector predominates, Russian corporations in other sectors have made significant investments abroad, securing important markets and establishing an external revenue base:

“Russian firms in the telecommunications sector expanded abroad for market-seeking purposes, strengthening their position in the neighbouring CIS region in particular. Accessing foreign expertise is also believed to have underpinned the globalization strategies of Russian telecommunications firms, although this was often achieved through strategic alliances with foreign technological leaders in the West, rather than through mergers and acquisitions, which were focused on companies in the CIS. In 2004, Russia’s leading mobile operator MTS acquired a 74 per cent share in Uzbekistan’s leading operator, Uzabunorbita. Russia’s second-largest mobile operator VimpelCom acquired a stake in Kazakhstan’s second-largest operator, KaR-Tel in 2005. VimpelCom also has operations in Tajikistan and the Ukraine, with plans to expand into Vietnam and Cambodia. Mobile TeleSystems (MTS) is a market leader in wireless communication in various CIS countries, including the Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, and Belarus. It is the largest company of Sistema Holdings, which itself has acquired licences to operate in India with plans to enter China and Bangladesh. VimpelCom is the most active globally expanding MNE among the Russian telecom firms.”

…

“MTS is the top non-natural resources-based company among Russian MNEs and Russia’s largest mobile phone operator. Sistronics, which is also owned by Sistema Holdings, is a major telecommunications provider as well as information technology specialist with operations in the CIS as well as the Czech Republic and Greece. Russian telecommunications firms are rapidly catching up with the natural resources-based and heavy manufacturing-based conglomerates on the global scene.

“In software and IT services, Russia is behind only the US in the number of companies that operate internationally in this sector. There are also some globally active technology-based Russian MNEs, particularly in information and communications technology. The anti-virus internet firm Kaspersky was created in 1997 and had developed a global presence by the end of 2005, expanding into 10 foreign locations including in Asia, Europe, and the US. Another Russian high technology firm, NT-MDT (Nanotechnology-Modular Devices and Tools) established an affiliate in Ireland in 2005 to carry out assembly, testing, and after-sales services as well as research and development. The Russian holding company GIS acquired French microelectronics manufacturer Altis Semiconductor in 2007….The Russian IT sector is now perceived to be highly stable and is consequently able to attract capital from private and institutional investors to fuel internationalization.” [pp.52-4]

Russia’s banking system (i.e., financial capital in the narrow sense of the term) is comparatively weak, yet it is fused with massive industrial capitalist enterprises in the energy sector (and presumably other sectors as well) and intertwined with a powerful state independent of all foreign domination. Russian finance capital has extended the reach of its banking sector abroad through overseas investments:

“Even in the poorly developed banking sector, the top five Russian financial institutions have subsidiaries in many countries. Russia’s largest MNE in the banking sector is Sberbank, which is a majority state-owned company that has two foreign affiliates in Kazakhstan and the Ukraine as well as cooperation agreements with agencies in the US, Hungary, and Israel. The much smaller VTB Bank specializes in foreign trade and has affiliates in several European countries including the UK, France, Germany, and Switzerland, as well as operations in Singapore, the Ukraine, and Angola. As noted above, there is a high degree of integration of production and distribution within Russia’s large extractive sector MNEs, one component of which is banking. Alfa Bank, for example, is banker to the Alfa Group, a conglomerate in the financial services and oil and gas industries. This reflects the strong link that Russian services-oriented investors have to the country’s dominant extractive sector. Russian banks are also now targeting consumers in Africa. Vneshtorgbank opened the first foreign majority-owned bank in Angola, and then moved into Namibia and Cote d’Ivoire. Renaissance Capital owns 25 per cent of the shares in Ecobank, one the largest Nigerian banks, with branches in 11 other African countries.” [p.54]

In the course of the 2000s, the Russian oligarchy transformed itself into the finance-capital bourgeoisie of an imperialist power. The process was assisted by the country’s military and geopolitical inheritance from the Soviet Union, which allowed an economically resurgent Russia, under the control of a strong state dominated by the oligarchs, to begin to reverse the encroachments on what it viewed as its spheres of influence, forcefully demonstrated in the 2008 war with Georgia that triggered the first round of our debate.

In November 2008, we sent a compilation of documents from both sides of the debate (then known as “Duckites” [Imps] vs. “Plats” [Nimps]) to our widely respected friend Murray, who responded with a short contribution in which he said he was unable to decide who was correct, suggesting that Russia was either a “proto-imperialist” or a “pariah-imperialist.” In a passage cited on more than one occasion by the Nimps, Murray wrote:

“In the last analysis what distinguishes a semi-colony from an imperialist country (of whatever rank) is the fact that, over the long term, the former suffers a net outflow of ‘value’ while the latter experiences a net inflow. These flows of value are mediated by several mechanisms – direct investment, portfolio investment, unequal exchange in world markets – that systematically favor more advanced capitalist countries, evincing high productivity, over more backward ones.”

It is worth recalling what Murray wrote immediately after this passage:

“But a set of further questions now suggest themselves: how ‘high’ does this ‘high productivity’ have to be to guarantee a ‘net inflow’ of value? Is it possible for some countries to occupy an intermediate position over the long term that involves neither significant net inflows nor net outflows (some sort of ‘semi-peripheral’ status, to use the language of ‘world-system theory’)? Are there not ‘natural factors’ that may, for a time at least, permit a net inflow of value (or at least block a net outflow) — for example, a conjunctural boom in primary commodity prices in resource-rich countries like Russia, Saudi Arabia or Venezuela? How ‘independent’ would the national bourgeoisies or ruling elites of such countries have to be to leverage such natural advantages in such a way as to escape a semi-colonial status? What ‘weight’ do we give to these various factors in assessing the location of a particular country within the imperialist-dominated world system?”

On the basis of the evidence then available (supplied in our discussion documents), Murray observed:

“In general, the data suggest to me that Russia’s economic development is not being distorted or ‘disarticulated’ in ways that are typical of semi-colonial formations. Russia is burdened neither by pre-capitalist social relations nor by a state beholden to foreign capital. The Russian bourgeoisie is as ‘independent’ as the bourgeoisies of the EU, indeed more so. Russia is currently a major holder of foreign currency reserves, thanks largely to its role as an exporter of natural gas and oil during a period in which energy prices skyrocketed. There is no meaningful sense in which we can say that Russia, as a capitalist state, has become a victim of ‘world imperialism.’ Indeed, it’s very likely that Russia has seen a net inflow of value in recent years (admittedly after many very difficult years in which Russian industry was laid waste). In short, Russia has escaped the fate that seemed possible after 1991: its relegation to a semi-colonial status.”

While also noting the role played by the decline of the established imperialist powers following capitalist counterrevolution in the Soviet Union, Murray explained how Russia was able to avoid subordination to the more advanced capitalist countries of the imperialist inner core:

“To understand how and why Russia escaped full subordination to world imperialism provides us with some clues as to what Russia is now and where it is going. In my opinion, Russia’s recent trajectory of ‘economic modernization’ and its emergence as either a ‘proto-imperialist’ or imperialist power owes much to the fact that it inherited from the Soviet workers state not only obsolescent industrial plant but a comparatively modern infrastructure, not only relatively low productivity but also a well-educated and highly skilled working class, and not only uncompetitive firms but an industrial rather than a primarily agricultural economy. Putin’s achievement was to reassert the role of the Russian state as the guardian and sponsor of a ‘responsible’ national bourgeoisie – one more concerned with long-term development than with the short-term profiteering that characterized the ‘oligarchs’ of the Yeltsin era.”

Murray wrote that he wished to see if Russia would be able to hold onto and deepen its strong position in the coming period before he would conclude that it was not simply a “proto-imperialist” state but a fully imperialist power (albeit a “pariah”):

“Does a decade of robust growth under an independent bourgeoisie allow us to declare that Russia is now an imperialist power? I’m tempted to say yes, above all because the Russian state has (somewhat realistic) aspirations to consolidate itself as a major player in the world imperialist system. But two important questions give me pause. The first is: can Russia sustain its present trajectory in the face of the strong headwinds of an intensifying global recession/depression? The second is: will the current economic crisis lead in the medium term to fundamental geo-political realignments within the world system and what effect could these have on Russia’s economic, political and military roles? I’m not sure anyone can answer these questions with any degree of certainty at the moment.”

Over the past five years, the Imps have argued that events seemed to demonstrate Russia’s continued and deepening “economic, political and military” role in the global imperialist order, e.g., Putin spiking a U.S.-led assault on Syria. The Nimps have responded mostly with assertions about Russia’s “defensive” posture tied to a weak economic position, and with documentation on low labor productivity/OCC and a dearth of competitive products in some industries.

While we have noted the problems with focusing exclusively on economic variables, and on one or two sets of economic indicators at that, we have agreed that a country’s imperialist status will, over time, manifest itself in a net transfer of surplus value (through various mechanisms) from the neocolonial countries in which it invests. Despite the serious problems with official FDI figures—in particular for Russia, whose outward foreign investment, as Dave’s recent contribution and my earlier contribution noted, is under-represented in the UNCTAD statistics—we have been using these figures as a very crude measure of capital export (and by implication surplus extraction). [See attached document—“FDI Figures and a Grain of Salt”.]

So what has happened over the past five years since Murray wrote his assessment? In terms of official FDI profile alone, has Russia become “more semi-colonial” or “more imperialist”? Below is a series of graphs I’ve put together, taking inspiration from Barbara’s reply to Roxie. They compile a large amount of FDI flow data from UNCTAD. There are four categories of country to which I compare Russia: (1) BRICS and other strong neocolonies/regional powers; (2) “petro states”; (3) the G7; and (4) smaller/weaker imperialist countries. For each of these categories, I look at (A) Outward FDI (which is an indicator of the absolute size of new investments abroad); (B) Net Outward FDI (which is an indirect indicator of the transfer of surplus value from abroad); and (C) Outward FDI as a percentage of GDP (which is an indicator of the weight that new investment abroad has for a country’s economy).

Just Another BRIC in the Wall?

Graphs 1A, 1B and 1C examine Russia in relation to the BRICS (excluding China because it is a DWS) as well as Turkey, Greece and Portugal, i.e., the more powerful neocolonial countries to which Russia has been likened in our debate. I have also included the G7 Average for comparison. The G7 is, of course, the group of the most advanced imperialist countries.

Note: In all of the graphs that follow, I am taking the FDI figures at face value (i.e., neither inflating them due to the problem of under-reporting Russian FDI, nor deflating them due to round-tripping, which as I note in the attached document is both difficult to quantify with accuracy for any imperialist country and a feature of all imperialist countries). If we’re using official FDI data for a comparative analysis, then that’s what we’re doing: it would be a bit of a cheat to arbitrarily deflate the figure for one of the countries (i.e., the country you wish to show is a weak performer) while implying that a similar procedure for some or all of the others is not appropriate (particularly when the evidence suggests that it would be appropriate, albeit extraordinarily complicated, to varying degrees). In any event, since the Nimps claim that at least Brazil also suffers from a two-thirds discount on FDI (and presumably many other neocolonial countries do as well), the relative gap between Russia and Brazil would persist on average.

[BT Editorial Note: FDI charts have been deleted in the interests of space, (with the exception of those for “Petro States,” i.e., 2A, 2B and 2C, because they featured in a subsequent dispute). Decker’s “conclusions” for each set of charts provides a reasonably accurate description of what was displayed.]

Conclusions

- From the mid-2000s onward, the absolute size of Russia’s outward FDI flow has been somewhere between that of the capitalist BRICS/strong neocolonies and that of the G7/first-tier imperialist powers.

- From the late 2000s onward, Russia’s net outward FDI has been positive (albeit much smaller than the G7 average) except for 2012 (when it dipped slightly into negative territory), while the net outward FDI of the capitalist BRICS/strong neocolonies has been mostly negative (and Brazil’s was significantly in the red).

- From the mid-2000s onward, Russia’s outward FDI as a percentage of GDP has been markedly higher (in relative terms) than that of the capitalist BRICS/strong neocolonies (with the exception of Portugal in 2011), whereas it has been roughly comparable to (and even exceeded) that of the G7 average.

‘Petro States’

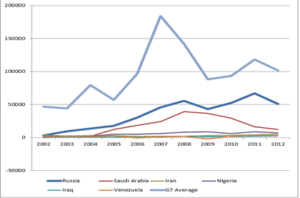

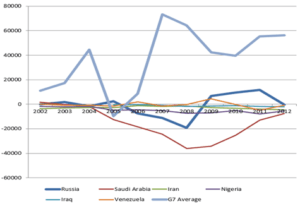

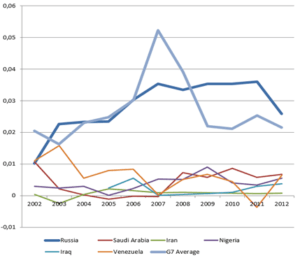

Graphs 2A, 2B and 2C compare Russia with a selected group of so-called “petro states,” to which the Nimps have also likened Russia due to the common heavy focus on the production of oil and natural gas, despite Russia having highly oligopolized manufacturing and telecommunications industries that export capital as well.

Conclusions

- From the mid-2000s onward, Russia’s outward FDI has significantly exceeded that of the other “petro states” (with the exception of Saudi Arabia, which Russia began to outpace only in the late 2000s).

- From the late 2000s onward, Russia’s outward FDI has moved closer to the G7 average as it leaves the “petro states” behind.

- From the late 2000s onward, Russia’s net outward FDI was positive (though it dipped slightly into the red in 2012), surpassing that of the “petro states,” which had a negative net outward FDI (except for Venezuela in 2009). Saudi Arabia was the worst performer of the bunch.

- From the mid-2000s onward, Russia’s outward FDI as a percentage of GDP has (in relative terms) greatly exceeded that of the “petro states,” while it has converged with (and sometimes surpassed) that of the G7.

2A: Outward FDI: Russia vs. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela + G7 Average (2002-2012) [USD at current prices and current exchange rates, millions]

2B: Net Outward FDI: Russia vs. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela + G7 Average (2002-2012) [USD at current prices and current exchange rates, millions]

2C: Outward FDI as a percentage of GDP [multiply by 100]: Russia vs. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela + G7 Average (2002-2012)

First-Tier Imperialists: G7

Graphs 3Ai, 3Bi and 3Ci compare Russia with the most advanced, first-tier imperialist countries (while Graphs 3Aii, 3Bii and 3Cii compare Russia with the average of those countries taken as a group, i.e., the G7).

Conclusions

- From the mid-2000s onward, the pattern of Russia’s outward FDI flow has roughly paralleled that of the G7 average.

- By 2007, Russia’s outward FDI surpassed (and has since remained above) the lower threshold of the G7 over the decade, though the country’s figure has been approximately half that of the G7 average, which fluctuated between $45 billion and $140 billion.

- The G7 average outward FDI figure is heavily influenced by the size of the U.S. figure, which in some cases was double or triple the G7 average. Since 2008, Russia’s outward FDI has been roughly similar to G7 countries other than the U.S. (especially when Britain and Japan are also excluded).

- By the end of the 2000s, Russia’s net outward FDI was positive (except for the small negative figure in 2012), though still well below the G7 average.

- Over the entire decade Russia’s outward FDI as a percentage of GDP was comparable to that of the G7 average, and since the end of the 2000s Russia has exceeded the G7 average.

- Over the entire decade Russia’s outward FDI as a percentage of GDP exceeded every individual G7 country at some point.

Second-Tier & Third-Tier Imperialists

Graphs 4A, 4B and 4C compare Russia with a handful of non-G7 imperialist countries, i.e., those that are commonly understood as second-tier or third-tier imperialist countries.

Conclusions

- Since the mid-2000s, Russia’s outward FDI has consistently exceeded that of Australia and New Zealand, and since 2009 that of Spain and often that of Belgium.

- From the end of the 2000s onward, Russia’s net outward FDI, which was positive except for 2012, was greater than that of Australia, New Zealand and Spain in every year and greater than that of Belgium in every year but one.

- Since 2009, Russia’s outward FDI as a percentage of GDP has exceeded the figure for Australia, New Zealand and Spain.

***

Although I have cited Murray’s assessment of our 2008 debate, I must add that I have no idea what he thinks of Russia today—for obvious reasons, I have not discussed the subject with him. I doubt he has studied the matter nearly as closely as we have in the course of our subsequent discussion, and naturally we were not appealing to him to arbitrate a dispute in our group. Nonetheless, I find it interesting to reflect on how he—and the rest of us to varying degrees—seemed to be framing the issue of Russia’s imperialist status back in 2008, i.e., rather tentatively. In that context, we had expected the coming period to confirm or disprove the thesis that Russia had emerged (or re-emerged) as an imperialist power.

If Russia was an independent “great power” within the global capitalist system in 2008 (at a minimum a “proto-imperialist” as Murray described it), the subsequent period has witnessed, not its regression into semi-colonial status, but further consolidation and deepening of its imperialist character. One of the economic measures of this character—capital export, reflected crudely in the FDI flow data illustrated above—confirms that Russia does not resemble capitalist BRIC countries or other strong neocolonial/regional powers, nor does it resemble the “petro states.” Instead, it most closely resembles other economically weak/small imperialist countries (some of which it surpasses), though in some instances Russia even resembles the first-tier imperialist countries of the G7 (with the exception of the U.S.). Overall, its convergence with imperialist countries began in the mid-2000s and became clear by the end of that decade. It was not halted by the global economic crisis.

Murray concluded his commentary with the following paragraph:

“Let me end with the following observation. The international working class has no interest in promoting Russia as a capitalist counter-weight to US imperialism. Furthermore, whether Russia is deemed proto-imperialist or pariah-imperialist, there is no clear basis for a defensist posture toward it. Nevertheless, revolutionaries have a responsibility to expose the lies of the imperialists and to distinguish between defensive actions and overt aggression. In the recent Georgia events, the bigger liars were the Georgians and their US backers. Assigning greater responsibility for this senseless mass murder to the Georgia-US axis than to Russia, however, should not be construed as ‘militarily defending Russia against imperialism’.”

Likewise, it is necessary for revolutionaries to condemn Western imperialists for backing the reactionary coup in Ukraine, and it is necessary for revolutionaries living in those imperialist countries to focus their fire against their “own” governments. There is, however, nothing progressive in Russia’s attempt to hold onto its spheres of influence. This fact should be even clearer given the trajectory of Russian imperialist development over the past five years.